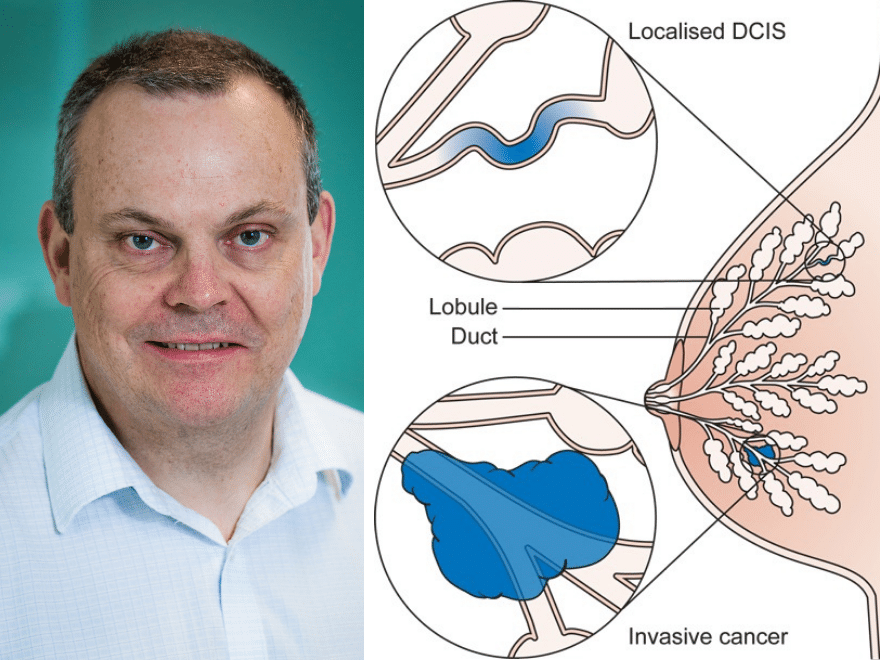

The Forget-me-Not 2 study is a recent study concerning women who have been diagnosed with Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). Here we talk to Dr. Anthony Maxwell, who until his recent retirement, was a Consultant Breast Radiologist, and Chair of The British Society of Breast Radiology.

Read on to find out more about DCIS and The Forget-me-Not 2 study’s subsequent findings on treatment.

What is Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS)?

Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) is a condition in which cancerous changes occur in some of the cells lining the milk ducts but these have not spread into the surrounding tissues, and at this stage the disease is unable to spread to other parts of the body. However, with time the DCIS is able to break through the membrane around the ducts in some women to become a potentially life-threatening invasive breast cancer. There has been considerable debate about how frequently this occurs and how seriously one should take a DCIS diagnosis.

What did the study show?

In the Forget-me-Not 2 study we examined the outcomes of 311 women who had been diagnosed with DCIS following routine mammography in the NHS Breast Screening Programme but for one reason or another had either not undergone surgery for the DCIS or had had surgery at least 6 months after a needle biopsy diagnosis. Information was obtained from several sources in order to provide as complete a set of data as possible. The study shows that the likelihood of developing an invasive cancer increases progressively with time after DCIS diagnosis and is related to the grade of the disease (how active it appears on microscopic examination). Approximately one third of women with high or intermediate grade DCIS developed invasive cancer in the affected breast within 10 years whereas fewer than 10% of women with low grade DCIS developed invasive cancer over the same time. Invasive cancer was more likely to develop in younger women and in those with large areas of DCIS. The majority of invasive cancers that developed in DCIS were relatively aggressive (grade 2 or 3) cancers.

Why is so little known about DCIS?

DCIS was a relatively rare diagnosis prior to the introduction of breast screening in the 1980s and 1990s, as it seldom causes symptoms but is usually visible on mammography. The standard treatment for the disease is surgical removal in view of the potential risk of progression to invasive cancer. This therefore makes it impossible to know for sure what would have happened if the disease had been left in the breast. Circumstantial evidence has been obtained from other studies, such as those looking at disease recurrence following surgery for DCIS, but to our knowledge this is the first study which has looked in detail at the outcomes of individual women who didn’t have surgery (or had delayed surgery) after a DCIS diagnosis

Why do we need to learn more about the outcomes for those who don’t have surgery?

The issue of ‘overdiagnosis’ in medicine has rightly been highlighted in recent years – this is the diagnosis and treatment of a condition that, had it not been diagnosed, would not have caused the patient harm within their lifetime. To a large extent this is a price we pay for modern medicine, for example a lot of people who have high blood cholesterol levels are treated by their GP with statins but only a relatively small proportion of them are prevented from having a stroke or heart attack. It has been suggested that a lot of DCIS is overdiagnosed. The Forget-me-Not 2 study suggests that for many women with low grade DCIS this is probably true, given that only around 10% of them developed invasive cancer in 10 years, and watchful waiting may be an appropriate management option for some women. However, only approximately 10% of women diagnosed with DCIS have low grade disease, and the study emphasises the importance of DCIS detection and surgical removal in the 90% of women who have more aggressive disease in order to prevent potentially life-threatening invasive cancers.

How do you distinguish between low grade and high grade DCIS?

DCIS is graded by pathologists on its appearance down the microscope in needle biopsy samples. Features that the pathologists look for include how quickly the cells are multiplying, how abnormal the individual cells appear, how they are arranged and whether some of them have died. It is recognised that there is significant variation between individual pathologists in the grading process, and this low reproducibility needs to be taken into account when considering treatment options.

What could this research mean for women being diagnosed with DCIS in the next 1, 5 and 10 years?

The findings support the concept of watchful waiting as a potential management option for women with low grade DCIS. However, a number of other studies are underway in several countries looking at this question, and we really need to see the results of those before moving away from surgery as the standard treatment. On the other hand, the importance of early detection and treatment of the more aggressive intermediate and high grade DCIS is confirmed, and hopefully this work will allow women to be reassured that surgical removal of the disease is the best treatment option in the great majority of cases.

How does your research contribute to our aims for Prevent Breast Cancer for future generations?

In addition to emphasising the importance of surgical removal of the DCIS in most cases, the study highlights the importance of its early detection by screening. Breast screening has received a fair bit of adverse publicity over the years with allegations of widespread overdiagnosis. This work reassures us that for the great majority of women with DCIS surgery is an appropriate option. It also suggests that we should regard the prevention of invasive cancer by the early detection of DCIS at screening with a similar importance to the detection of cancers that are already invasive, in much the same way that the cervical screening programme aims to detect cervical cancer before it becomes invasive and potentially life-threatening.

What did you enjoy most about being a researcher?

I have recently retired and am no longer actively involved in research. I did however particularly enjoy the buzz of being involved in ground-breaking collaborative studies of the prevention, early diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer and being able to make a contribution to improving the care of patients in the future.

About Prevent Breast Cancer

Prevent Breast Cancer is the only UK charity entirely dedicated to the prediction and prevention of breast cancer – we’re committed to freeing the world from the disease altogether. Unlike many cancer charities, we’re focused on preventing, rather than curing. Promoting early diagnosis, screening and lifestyle changes, we believe we can stop the problem before it starts. And being situated at the only breast cancer prevention centre in the UK, we’re right at the front-line in the fight against the disease. Join us today and help us create a future free from breast cancer. If you have any questions or concerns, email us today.

About Prevent Breast Cancer

Prevent Breast Cancer is the only UK charity entirely dedicated to the prediction and prevention of breast cancer – we’re committed to freeing the world from the disease altogether. Unlike many cancer charities, we’re focused on preventing, rather than curing. Promoting early diagnosis, screening and lifestyle changes, we believe we can stop the problem before it starts. And being situated at the only breast cancer prevention centre in the UK, we’re right at the front-line in the fight against the disease. Join us today and help us create a future free from breast cancer. If you have any questions or concerns, email us today.